Back to the future

A month after the CIBSE Conference and Exhibition, CIBSE Communications Executive Matt Snowden takes a look back at the highlights of the session 'Are you ready for a digital future?' and examines what we learned.

When we take a step back and review the engineering industry

it’s easy to take a look at the past and the future. We can look at the

decisions and plans we made a week, a month or a year ago and take lessons from

the good and bad things that resulted, and promise to learn from them. That’s

all part of planning for the future, where we’re confident that these

experiences will help us to avoid making mistakes and achieve our objectives.

What is much harder is examining what we are doing right now,

particularly where technology is concerned, mostly because of a lack of data.

At a time when new technology available to the engineering sector promises to

revolutionise our jobs as much as when the computer replaced the drafting desk,

it seems impossible to imagine that this might be holding us back rather than

pushing us forward.

|

| Talking about digital issues can focus too much on the tech, and not enough on the user |

That’s exactly what was discussed at the CIBSE Conference

and Exhibition, during the session ‘Are you ready for a digital future’, but

rather than focussing on the ‘business end’ of the issue – the technology

itself – the session focussed on the ‘back end’ – the supply chain that is

trying to use it.

The result was some interesting points about what the supply

chain actually wants from digital engineering, and how companies can overcome

their own shortcomings to take full advantage.

Mike Darby, CEO & Co-Founder of Demand Logic, made a

great point early on about the sheer volume of data available to engineers in

the modern world. A lot has been said about big data in just about every

industry there is, but built environment professionals are at the forefront of

the biggest connected devices in the world – the buildings we live and work in.

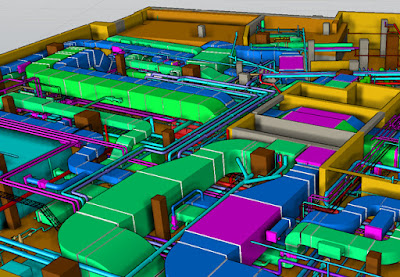

He calculates that there are over 170,000 BIM data points in

a new building like 20 Fenchurch Street (the Walkie Talkie) alone, bringing in

spreadsheets worth of data every day, but that the human interface with this

data creates a bottleneck. Every byte of that data is wasted, along with the

resources expended to gather it, if it is not stored and used correctly at the

user end. This amounts to a lot of waste, both potential and actual, and a lot

of money thrown away as a result.

|

| The 'Digital future' panel in action at the CIBSE Conference |

One of the issues at play was raised afterwards by panellist

Dave Mathews, a Partner at Hoare Lea, who said that we’re just not designing

user-friendly systems that give simple feedback about their performance. This

is an obvious problem, because users can’t act on what their building is

telling them about its performance if they can’t understand what it’s telling

them. This part is the responsibility of engineers, who can demonstrate their

value to a project by working with the other stakeholders and the occupants to

explain how a building works and why.

|

| The job of the engineer shouldn't stop at handover |

The job of the engineer doesn’t end when the keys to the

building are handed over and everybody has moved in. Alex McLaren of

Heriot-Watt University was on the panel, and believes that it’s her

responsibility as an engineer to revisit the project periodically to check up

on the tenants, and to see what lessons she can learn by the project in-use as

well. According to Mike Darby, often the people in charge of maintaining the

building and its performance just aren’t trained to a high enough standard to

get the best use out of its systems.

By sticking with a project to make sure that everybody has

enough information to run it properly afterwards, an engineer can ensure that

issues that aren’t picked up in the six-week commissioning period don’t come

back to haunt them later on. This can simply mean a handover period to explain

why certain systems exist and how they work, or it can even mean a more

in-depth training period to bring the maintenance staff up to speed. This

sounds like a lot of work but, of course, there’s something in it for the engineer

too.

As Alex McLaren said in the panel: ‘Who remembers the engineer after the

end of a project?’ You may not have your name stamped on the building like an

architect would, but you can demonstrate continuous value to the project way

beyond delivery by ensuring it works well.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment