Setting new benchmarks

Display Energy Certificates (DECs) were introduced by the UK Government in 2008, in order to demonstrate a more transparent approach to how public buildings perform from an energy efficiency perspective, and thus their value-for-money to the taxpayer. However, in energy efficiency, the eight years since their introduction may as well be 100 in terms of how energy efficiency in practice has moved on. CIBSE Research Associate in Energy Benchmarking Sung-Min Hong of University College London (UCL) writes below on his research into how the methodology behind DECs might be updated

When a consultation on the Display Energy Certificate scheme was published by the Department for Communities and Local Government in February 2015, I was surprised to say the least. At that point, I had just completed a four-year long doctoral program on the very topic of benchmarking supported by data from the DEC scheme. I had analysed more than 120,000 DEC records for assessing the energy performance of public sector buildings, and it was invaluable for completing the study. And it is from this experience that I had come to appreciate how valuable the scheme is for understanding the stock and benchmarking their energy performance.

It was also evident how valuable such framework would continue to be if we were to derive benchmarks that are based on large empirical data. So it wasn't very exciting to realise that a few options mentioned in the consultation were either to ‘do nothing’ or ‘abolish’ the DECs for reducing burden of compliance, without any options for making it better. It also reminded me of conversations I had with people like Bill Bordass about the history of benchmarking in the UK and challenges they had faced over the past decades. It was only after reading the consultation document that I truly understood what they meant and realised the complexity surrounding the topic.

A key challenge that we are facing at the moment is therefore to acquire empirical data that is large and comprehensive enough to represent various groups of the building population. An analysis of schools showed that uncertainties associated with a statistic or a benchmark considerably reduced until sample sizes reached close to 300 (Hong et al. 2014). Although it may sound small, getting such sample which is also representative of a particular group can be quite challenging, especially when dealing with such a heterogeneous stock. Once such data is available, revising benchmarks, or at least renewing the figures and refining classifications, would be a relatively simple task.

What’s more is that many people who I was fortunate enough to meet were very positive about the project and to support it wherever possible by sharing their data. The most recent of these, and a very positive experience, was with the Greater London Authority (GLA). The Mayor of London’s Business Energy Challenge (BEC) has been organised by the GLA since 2014 to encourage higher levels of efficiency in businesses. Each year participating businesses are required to submit energy consumption data and a host of other contextual information on their premises. With help from the GLA, we were able to gain access to data on close to 1,000 premises in the private sector, which had not been previously available at such scale and detail.

The work showed that there were growing number of businesses participating in the BEC and that many of them were becoming more energy efficient. Also, they were generally more intensive in electricity use compared to CIBSE TM46 benchmarks whereas heating consumption was less intensive. Interesting thing is that a similar pattern was also found in the public sector in the analysis of DEC records (Hong & Steadman 2013).

Since April 2015, I have been working on a three-year project called ‘Benchmarking and Assessing the Energy Performance of UK non-domestic Building Stock’. This CIBSE and UCL sponsored project is an attempt by both organisations to drive things forward. It has two key aims but I will focus on the first one in this blog. The first aim, which is also a precursor to the second, is to review and refine the existing energy benchmarks in CIBSE Guide F, whether it be the classifications or the benchmarks themselves.

If we look at the historical approaches to benchmarking in the UK, most energy benchmarks such as those presented in CIBSE Guide F that are publicly available are statistical in nature, except for some exceptions such as those presented in Energy Consumption Guide 19 that were based on a bottom-up approach (Bordass et al. 2014; Action Energy 2003).

So for a large part of the past 10 months much of my effort has been focussed around meeting people in various sectors trying to get as much data as possible. During this period it was very encouraging to see a growing trend in so called ‘big data’ on buildings becoming available across public and private sectors. It appeared as though there was a growing number of organisations who had been and were planning to regularly collect data as part of their initiatives to improve energy efficiency.

One of the things that I am really looking forward to is to observe how such pattern changes over a long period and to identify factors that contribute to such changes as more and more empirical data become available in the future. Insights gained from such studies would be invaluable for developing a framework for producing benchmarks that are representative of the stock, relevant to a diverse range of buildings used in different ways, and sustainable.

There are however challenges that lie ahead before the revised benchmarks can be made publicly available. Many of these are related to the data itself. From what I have noticed over the past 5 years, the vast majority of data isn't often stored in a centralised location, even within the same organisation, and is very likely to be stored in formats that are not compatible to other datasets.

Establishing a standardised data storing protocol is probably a way to make things easier for the future, but developing a consensus and rolling it out across the sectors are likely to take time. Also, data that is collected and processed at the moment is likely to be short of representing all groups in the building population, mostly due to the vast size and diversity of characteristics that influence demand for energy. Despite the challenges however, what is exciting about the current process is that having a centralised database will give us an opportunity to continuously assess what we know about data and the population,and this will provide a basis for making continuous improvements.

Going forward, 2016 is likely to involve continued work on data gathering and also a chance to start working on the second aim of the project. The second part will focuson understanding the influences that intrinsic features specific to a building or an activity type have on demand for energy. The hope is then that the findings will help us explore how benchmarking could become more relevant for buildings in different contexts. Having said that, there is still a lot of work to do before anything specific can be discussed. Please keep visiting the CIBSE Technical pages for updates on the progress of the project.

References

Action Energy, 2003. Energy Consumption Guide 19: Energy use in offices, London, UK.

Bordass, B. et al., 2014.

Tailored energy benchmarks for offices and schools, and their wider potential. In CIBSE ASHRAE Technical Symposium. Dublin, Ireland, pp. 3–4.Hong, S.M. et al., 2014.

A comparative study of benchmarking approaches for non-domestic buildings: Part 1 – Top-down approach. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment, 2(2), pp.119–130.

Hong, S.M. & Steadman, P., 2013. An Analysis of Display Energy Certificates for Public Buildings 2008 to 2012. Available at: https://www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/energy/news/display-energy-certificates.

When a consultation on the Display Energy Certificate scheme was published by the Department for Communities and Local Government in February 2015, I was surprised to say the least. At that point, I had just completed a four-year long doctoral program on the very topic of benchmarking supported by data from the DEC scheme. I had analysed more than 120,000 DEC records for assessing the energy performance of public sector buildings, and it was invaluable for completing the study. And it is from this experience that I had come to appreciate how valuable the scheme is for understanding the stock and benchmarking their energy performance.

It was also evident how valuable such framework would continue to be if we were to derive benchmarks that are based on large empirical data. So it wasn't very exciting to realise that a few options mentioned in the consultation were either to ‘do nothing’ or ‘abolish’ the DECs for reducing burden of compliance, without any options for making it better. It also reminded me of conversations I had with people like Bill Bordass about the history of benchmarking in the UK and challenges they had faced over the past decades. It was only after reading the consultation document that I truly understood what they meant and realised the complexity surrounding the topic.

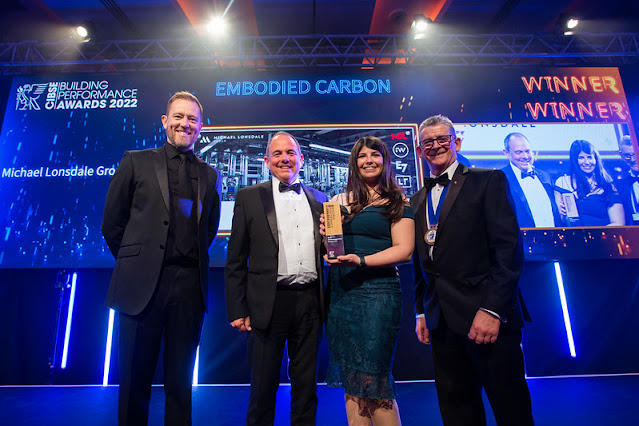

|

| 2016 Building Performance Award winner Wilkinson Primary School by Architype is one such high performing public building |

What’s more is that many people who I was fortunate enough to meet were very positive about the project and to support it wherever possible by sharing their data. The most recent of these, and a very positive experience, was with the Greater London Authority (GLA). The Mayor of London’s Business Energy Challenge (BEC) has been organised by the GLA since 2014 to encourage higher levels of efficiency in businesses. Each year participating businesses are required to submit energy consumption data and a host of other contextual information on their premises. With help from the GLA, we were able to gain access to data on close to 1,000 premises in the private sector, which had not been previously available at such scale and detail.

The work showed that there were growing number of businesses participating in the BEC and that many of them were becoming more energy efficient. Also, they were generally more intensive in electricity use compared to CIBSE TM46 benchmarks whereas heating consumption was less intensive. Interesting thing is that a similar pattern was also found in the public sector in the analysis of DEC records (Hong & Steadman 2013).

|

| CIBSE Guide F on Energy efficiency in buildings |

If we look at the historical approaches to benchmarking in the UK, most energy benchmarks such as those presented in CIBSE Guide F that are publicly available are statistical in nature, except for some exceptions such as those presented in Energy Consumption Guide 19 that were based on a bottom-up approach (Bordass et al. 2014; Action Energy 2003).

So for a large part of the past 10 months much of my effort has been focussed around meeting people in various sectors trying to get as much data as possible. During this period it was very encouraging to see a growing trend in so called ‘big data’ on buildings becoming available across public and private sectors. It appeared as though there was a growing number of organisations who had been and were planning to regularly collect data as part of their initiatives to improve energy efficiency.

|

| Collecting real-time data on energy usage is an emerging efficiency strategy |

There are however challenges that lie ahead before the revised benchmarks can be made publicly available. Many of these are related to the data itself. From what I have noticed over the past 5 years, the vast majority of data isn't often stored in a centralised location, even within the same organisation, and is very likely to be stored in formats that are not compatible to other datasets.

Establishing a standardised data storing protocol is probably a way to make things easier for the future, but developing a consensus and rolling it out across the sectors are likely to take time. Also, data that is collected and processed at the moment is likely to be short of representing all groups in the building population, mostly due to the vast size and diversity of characteristics that influence demand for energy. Despite the challenges however, what is exciting about the current process is that having a centralised database will give us an opportunity to continuously assess what we know about data and the population,and this will provide a basis for making continuous improvements.

|

| Current benchmarks do not represent enough diversity in building types, sizes or ages |

References

Action Energy, 2003. Energy Consumption Guide 19: Energy use in offices, London, UK.

Bordass, B. et al., 2014.

Tailored energy benchmarks for offices and schools, and their wider potential. In CIBSE ASHRAE Technical Symposium. Dublin, Ireland, pp. 3–4.Hong, S.M. et al., 2014.

A comparative study of benchmarking approaches for non-domestic buildings: Part 1 – Top-down approach. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment, 2(2), pp.119–130.

Hong, S.M. & Steadman, P., 2013. An Analysis of Display Energy Certificates for Public Buildings 2008 to 2012. Available at: https://www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/energy/news/display-energy-certificates.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment